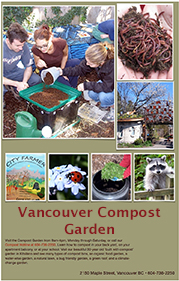

Canada: Composting teacher at City Farmer adapts classes amid pandemic, worm shortage

“It’s a strangely popular topic. People love it,” he said.

By Marc Fawcett-Atkinson

National Observer

November 9th 2020

Excerpt:

Usually, she’ll give the class a “worm bin,” a lidded plastic container with about 40 worms. That’s a bit less than what most households would use, but it’s perfect to teach them the basics. That includes making sure the worms have enough water, as their skin needs to be moist for them to breathe, and that food scraps are placed in the right part of the bin (the corners).

In pre-pandemic times, she’d work with about 60 classes throughout the school year, and about half of them would keep the compost bin for the duration of the academic year. That’s ideal, she explained, because it lets the kids see the composting process in its entirety.

It’s a model that has been going on since the early 1990s, explained Mike Levenston, founder of City Farmer.

“For some people, worms are very icky. Other people, they’ll tell you they’ve gone down the street after rain, and they feel so bad for these worms that are on the sidewalk, they pick them up and put them in the ground so they’re safe. There’s a strange connection,” he said.

A connection that generations of Vancouver kids have experienced first-hand. Levenston said that he regularly meets adults who remember the worm composting class they took when they were kids in elementary school.

It’s a passion that is particularly easy to foster because worms are so easy to care for. Unlike chicks and other common class pets, worms can go several days without needing fresh water or food, Lucy explained.