Canada: BC First Nations reawaken an ancestral practice: agriculture

“They would take much of their food off the land in terms of hunting and their kitchen garden if they could. And, of course, like white settlers, they would preserve food for the winter. They would can their peas and preserve their vegetables and have root cellars, and so on.”

By Marc Fawcett-Atkinson

National Observer

November 25th 2020

Excerpt:

“There was an agriculture here that wasn’t immediately recognizable to Europeans,” he explained. For instance, Coast Salish people on the province’s south coast used controlled burns to maintain camas and wild potato plantations, but these well-tended clearings weren’t recognized by early Europeans as cultivated fields. As more Europeans arrived in present-day B.C., those practices started adapting to a new import: potatoes.

The potato trade wasn’t limited to the north coast. Lutz said communities from southern Vancouver Island to Alaska picked up the potato trade and usually grew them in fertile and moist pockets of land scattered across their territories.

That trade came to a halt in the late 1800s when the Canadian government started forcing Indigenous people onto miniscule reserves. And because the potato patches were rarely recognized as such by the white surveyors who mapped reserve boundaries, most were left out. The reserve system also made it difficult for Indigenous people provincewide to profitably practise European-style agriculture — like ranching or crop farming — because most of B.C.’s water rights had been stolen by settlers and reserves were rarely large or fertile enough for farming.

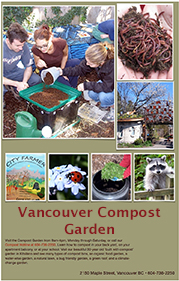

While the reserve system and other federal policies made farming commercially almost inaccessible to most Indigenous people in B.C., growing food was still a widespread practice, Lutz explained.

“In the early 20th century, you see a lot of extensive kitchen gardens, people who are living out of their gardens. In part, this is an economic necessity. Indigenous people in large parts of the province didn’t have much access to the cash economy,” he said.