Canada: Driving Down Emissions: The Road to Sustainable Urban Food Systems

Urban agriculture offers a direct solution to the emissions created by industrialized agriculture by shortening supply chains, and reducing emissions from land-use changes, production and transportation.

By Madeline Greenwood

Envr 400, McGill University

7 Dec. 2018

Excerpt:

Changing Systems though Urban Agriculture: Examples from Montreal

The social and economic systems created by our governments and corporations as a means to provide for our populations, reinforce both industrial agricultural practices and the underlying worldviews through dynamic and political transnational relations. In order to comprehensively tackle the obstacles introduced by this system, UA strategies must attend to its complexities, intervening with similarly sophisticated intention to alter not only symptoms, but foundations of the problem. Using the principles of leverage points, a framework popularized by Donella Meadows in 1999, the following section will attempt to highlight the potential of UA to accomplish this feat by combining multiple implementation methodologies. Figure 1 of the Annex makes explicit the corresponding leverage points outlined through the following UA strategies.

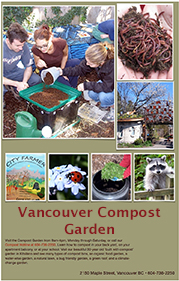

Montreal proves an interesting case study through which to assess the viability of UA as a solution, because of the multifaceted interventions already in place. Despite the climatic limitations to providing year-long production conditions, Montreal has an extensive network of 97 community gardens throughout the boroughs, as well as thriving market solutions, such as Lufa Farms, that allow people to choose how they participate in UA, be it the contribution of time, money or space (Reid, n.d). Moreover, a 2014 study discovered that the city has the spatial capacity to “meet the city’s [annual vegetable] demands” without necessitating high intensity, or high energy cultivation models (Haberman, 2014). This indicates that expansion of these already considerable UA efforts is physically viable, allowing the next section to proceed under this pretense.

UA offers a direct solution to the emissions created by industrialized agriculture by shortening supply chains, and reducing emissions from land-use changes, production and transportation. By using vacant lands and rooftops space, “urban farmers [already] supply food to 12% of the world’s population” (Ladner, 2012). This shift in “the structure of material stocks and flows,” from global to local trade represents a shallow leverage point, however variability in the manifestation of UA in practice influences its capacity to invoke deep leverage points (Meadows, 1999). The success of UA projects as a long-term and sustainable solution depends on the employment of multiple types of interventions, decided based on the values, needs and constraints of individuals and communities. Assuming that all people would like the opportunity to participate in some form of UA, investing in both community and market-based solutions can lift barriers to access for differing societal groups. Strengthening the capacities of communities to self-determine the structural details of their food system not only works toward dismantling current systems, but also toward shaping UA solutions that foster shifting paradigms for lasting system-level changes.

Full paper below.